Edoardo Ponti (Geneva, 1973), son of Sophia Loren and producer Carlo Ponti, is a director, screenwriter and producer, occasionally also an actor. In 2002 he made his debut in the cinema with Extraneous Hearts, continuing his career with Coming & Going and the award-winning short films Away We Stay, The Night Shift the Stars Do It, from the homonymous story by Erri De Luca, and Human Voice, by Jean Cocteau, presented in Venice. His most recent film, The Life Ahead, based on Romain Gary's novel of the same name and starring Sophia Loren and Renato Carpentieri, was one of Netflix's biggest hits in 2020 and was nominated for a Golden Globe for Best Foreign Film. In the second half of the 90s, Edoardo Ponti was the personal assistant of Michelangelo Antonioni, who had just been awarded the Academy Award for Lifetime Achievement, for the realization of two projects that were later faded: Just to Be Together, strongly desired also by Jack Nicholson, and the science fiction Destination: Verna, which would have seen Sophia Loren protagonist.

What are your first memories of Michelangelo Antonioni?

Michelangelo was an artist whose name was mentioned many many times in my house while I was growing up: I knew the name ‘Michelangelo Antonioni’ before I knew what exactly Michelangelo Antonioni did as a profession. When I was 4 or 5-year-old I only knew that he was my father Carlo’s collaborator, my father’s friend and that my father was very proud of the work he was doing with him. Carlo Ponti undoubtedly was a man who was very objective towards his own work, he did not naturally express pride or excitement for what he did unless he was sure of its value, and this was undoubtedly the case of the movies that he was making with Michelangelo Antonioni.

What was the first Michelangelo Antonioni – Carlo Ponti movie you saw, and how old were you?

Only when I was older I saw their first collaboration, which was Blow-up. I watched that movie when I was about 15-year-old, in Madrid, from a VHS that a friend of mine had. He was hanging out with other friends, I did not want to go out so I picked up that VHS. I remember that evening very clearly: I started watching Blow-up at 6 o’clock P.M. and it ended at about 8, but I was so mesmerized and hypnotized that, when it ended, I saw it for the second time immediately.

Blow-up, Michelangelo Antonioni (1966)

Why did Blow-up impress you so much?

It was the first time that I saw a film that tried to convey all those silent but so evocative abstractions that we all do experience in life, between people. The dynamics between people are so hard to express and explain, yet Michelangelo was able to convey them into a film, through his sensibility, through his intelligence, through his aesthetic mastery of film media, through the way he used to cut his movies. After Blow-up, I saw movies differently: there was, to me as a moviegoer, a ‘Before Blow-up’ and an ‘After Blow-up’. That evening I called my father and I told him I saw it: he was surprised I had not watched it yet, but you know, when you are a kid and your father is proud of something, you almost refuse it as a rebellion; I needed to see Blow-up in my own way, with my own time. Since then, the cinema Michelangelo Antonioni entered my heart, my body, all my senses.

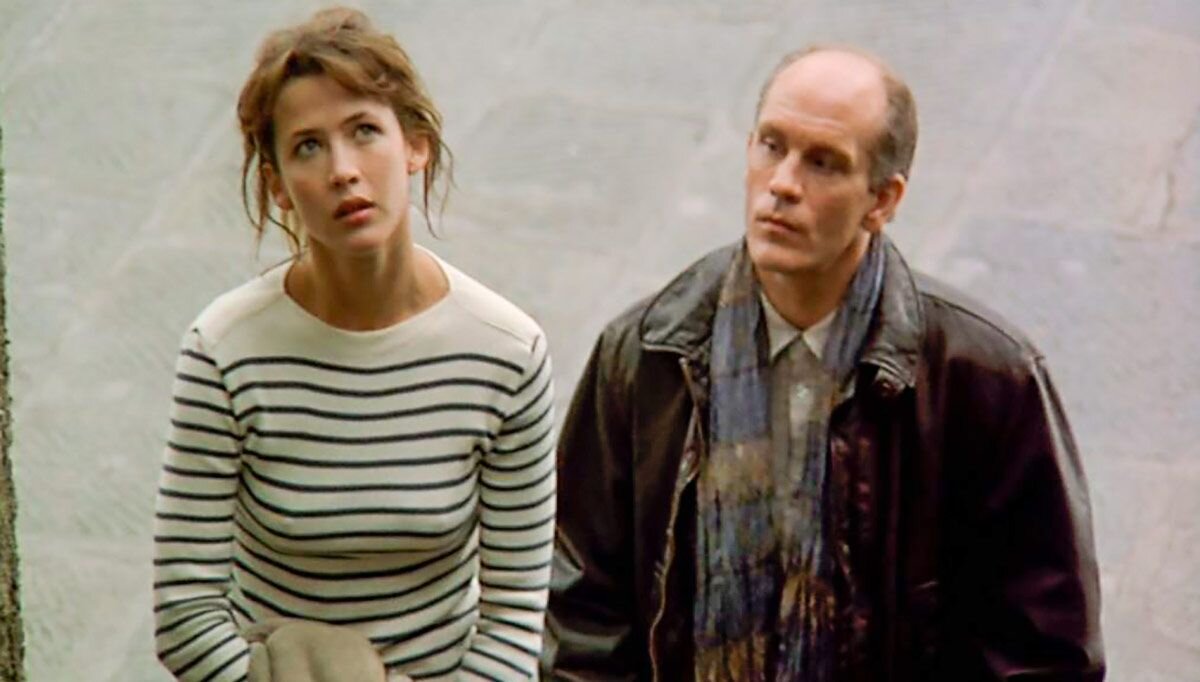

Michelangelo Antonioni and Vanessa Redgrave on the set of Blow-up

After Blow-up, what were Michelangelo Antonioni’s movies that you saw next?

Once I entered the world of Antonioni through Blow-up, the next movies that I saw were not Zabriskie Point or The Passengers, the other two produced by my father. I actually wanted to go earlier and see his previous movies, such as L’avventura (The Adventure), L’Eclipse (L’eclisse), La notte (The Night), Il grido (The Cry). It’s so funny because there is a common criticism of Antonioni’s body of work as if his movies ‘leave the audiences cold’. I really never felt that, I rather always sensed the opposite of that: in his works, to me, there is an immense humanism. Through his movies Michelangelo Antonioni strived to capture the immaterial between two people, what cannot be communicated between them: there’s nothing more human than an artist who has the ambition to shine a light between two characters, two human beings after all. I started watching his movies as a teenager, at the times of the first dates, of the first girlfriends, and it was interesting to understand my own experiences through the prism of what Antonioni depicted in his movies. Antonioni’s movies told me the truth: relationships are so difficult, the ability to connect with another human being is not immediate; but precisely because his characters have a hard time relating to each other, you know they have a desire to connect. This desire to connect shows that Michelangelo was a man always seeking those connections. Something that Antonioni always loved to do – I know this from his wife Enrica – was to watch thriller movies: he may not like them, but he liked to watch them. Something that Michelangelo thought me is how to tell a story, which is, in essence, a dramatic story with dramatic components, through the prism of a thriller, how to use almost a formal iconography of a thriller at the surface of a drama. Growing up while watching his movies, having conversations with Enrica while I was collaborating with Antonioni later as his assistant, I saw this very clearly.

La notte, Michelangelo Antonioni (1961)

In the Nineties, Michelangelo Antonioni was already debilitated by his illness, but he had also won an honorary Academy Award in February 1995 and, later that years, presented to the Venice Film Festival the feature film Beyond the Clouds, shot in collaboration with Wim Wenders. When and why you started collaborating with Antonioni as his personal assistant?

I started collaborating with Michelangelo because he came to Los Angeles, to direct the movie Just to Be Together (Tanto per stare insieme) and I was a film student at the University of Southern California, in the second or third year of Fine Arts. Michelangelo and Enrica wanted to pay a visit to my parents and came to our house in L.A. for lunch, and, after spending time with me, he and his wife, because of my bilingual nature and the fact that I was a film school that loved his work and I was basically “part of the family”, proposed me to assist Michelangelo through the course of pre-production and the shooting of Just to be Together. I immediately accepted, and that was how it came about. It was like a part-time job as I went to university!

Your collaboration with Michelangelo Antonioni focused mainly on the preparation of the movies which actually were never shot, Just to Be Together, inspired from a short novel by Antonioni himself, and Destination: Verna freely adapted from a science-fiction novel by Jack Finney. What was Just to Be Together about and what were your tasks in the preparation of the movie?

Just to Be Together revolved around a love triangle set against the vacuum of Los Angeles in the early Eighties. It was written by Michelangelo and Rudy Wurlitzer. When I entered production, they were already in the phase of location scouting and casting. What was really amazing of the work with Michelangelo, something which later as a director I completed adopted is the fact that normally filmmakers adapt the world and the locations to the needs of the script and of the scenes; Michelangelo did exactly the opposite: it was through the exploration of the real world, the explorations of locations, that he shaped the scene in their final form. People believe that Michelangelo controlled in a very formalistic way the sceneries of his movies, but it was the opposite: his movies were shaped by the mood, by the actual locations, by the sensation you feel as you enter a potential location and you tell yourself ‘you know what? this is way better. Michelangelo’s curiosity, mixed with his flexibility, was something that really impressed me because it showed that he was a man that always in search of an authentic experience. His vision was always shaped by what ‘fate’ offered him, as preparing the next movie. As a young film student growing up, that was an immense lesson.

During the preparation of Just to Be Together, how did you connect and communicate with Michelangelo Antonioni, and how your relationship evolved assisting him in the pre-production of the movie?

He and I connected over many many aspects of our personalities, one of them was humour: I made him laugh so much. When I became his friend he had already suffered his stroke, he would speak but it was not easy for him: I was having a strong sense of what he wanted to say, for some reason I had this strong connection with him. When we were preparing Just to Be Together, I would attend together with Antonioni the meetings with the actors and, as he would speak in Italian, I would translate in English not only Michelangelo’s few words but what he wanted to say: due to the stroke he was not able anymore to articulate a wide vocabulary and already the fact that he could somehow express himself was itself a miracle. Despite his objective disability, Michelangelo Antonioni still had an indomitable desire to live, to communicate, to express himself as a filmmaker and to create. It was amazing: everybody else in his conditions would have only stayed at home and dreamed about the life he could live; he instead lived all his lives, until the very end. The connection I had with him helped also with actors, with producers, with designers: I was there, over the course of the weeks, the months, and this established a very strong bound between us.

Having worked with him in the preparation of both Just to Be Together and Destination: Verna, how have you witnessed that Michelangelo Antonioni set up the location scouting of his movies?

For Verna, I was not involved in the location scouting, but for Just to Be Together Michelangelo and I went everywhere in the area of Los Angeles and Palm Springs. When something was right – when a location felt right – Michelangelo got moved emotionally. He would almost cry. Those weren’t tears of sadness, of course, it was just the fact that a location that felt right truly hit him on an emotional level, and his psychical expression of something feeling right was being emotionally moved by it. Michelangelo Antonioni was very free and spontaneous in the location scouting: for example if we had to meet at 10 A.M. a person who would have to show us his house for the movie, but on the way there Michelangelo glimpsed a scenery that intrigued him, he urged to stop and, on the way to the planned location, we would end up finding four more locations who were the potential settings for other scenes. In other words, he never limited his creative expression, he was always on, so that if on the way to somewhere another spot cut his eye, that would also have added to the location scouting. Each day with him was a day of true exploration. Sometimes, we would walk into a house and he would surely look to the house, but also open drawers and closets because he was so interested in the energy of the people living there. Everything could become something, to him, with him. When scouting a location, we weren’t scouting a location, we were scouting anything between A and B. Drivers and organizers got always crazy, but it did not matter to us, the priority was to respect Michelangelo and his vision.

Just to Be Together was meant to be the ‘reunion’ of Michelangelo Antonioni with Jack Nicholson, who had starred in Antonioni’s 1975 cult The Passenger and who delivered the maestro his honorary Academy Award in 1995. What role was Jack Nicholson supposed to have in Just to Be Together? What do you remember of the meetings between Antonioni and Nicholson?

I don’t remember if Jack Nicholson was supposed to act in it; surely, due to an insurance request, given to Michelangelo’s conditions Jack Nicholson was supposed to fill the position of a ‘stand-by’ director, the same that Wim Wenders filled on the set of Beyond the Clouds. In the final part of his career, there should have always been a ‘stand-by director’ on his side, but surely Michelangelo would have directed any frame of Just to Be Together, as he did with Beyond the clouds. At the time, Jack Nicholson had directed several movies on his own, and notably had starred as the lead in Michelangelo Antonioni’s The Passengers, so he seemed the perfect choice as backup director. I remember being there for their first meeting after years they haven’t seen each other. It took place in the Monkey Bar, an L.A. place that Nicholson owned. Jack Nicholson was to my right, Michelangelo was to my left and I was in the middle, ready to translate but actually, there was no need to: even though they did not quite speak the same language – Michelangelo of course spoke English, but was impeded by the stroke, Jack did not speak not a word of Italian – they managed to understand each other on a totally different level, a mutual understating that came from having worked together. It was kind of an explosive meeting, somewhat intimidating too, for a film student in his twenties being in presence of these two masters seeing each other for the first time many many years, but it was also a kind of great. I remember feeling exhausted after the meeting, as until that moment I had been so focused on the translation and about helping them in any way I could. These are the situations that shape you, as a young person.

What was planned to be the main cast of Just to Be Together, and why the movie was canceled?

If we had a cast, we would have shot the movie. One of the problems that affected the pre-production of Just to Be Together, and that eventually caused the cancelation of that movie, it was the fact that we never managed to assemble together, and all in the same shooting period, the cast that Michelangelo wanted. That was really heart-breaking, because he put so much time, so much energy into that movie, and, given his conditions, also so much courage, and the fact that we could never find the right leads it was really devastating. That was, as a young filmmaker, an important lesson: no matter who you are, how famous you may be as a director, how influential your body of work is, this does not mean that making a movie is automatic. There are obstacles that go beyond even your stature, and that was a huge lesson of humility.

The following Destination: Verna had to be an atypical and authorial science-fiction movie, starring as protagonists your mother Sophia Loren, Anthony Hopkins, Naomi Campbell and Kim Rossi Stuart. In 1998 Sophia Loren declared to La Repubblica that Destination: Verna would have finally fulfilled a promise of working together that she and Antonioni had kept renewing for thirty years, and the article credited you as the ‘middleman’ of the rapprochement between the two of them. How the involvement of your mother took place? Had she already started preparing the role, upon the indications of Antonioni?

My mother never went as far as character preparation, because the script was not ready yet: it was a script in development, and then, as it often happens, once the script gets developed another project gets offered to somebody and you end up doing something else, and so on. Making any movie is a miracle, and by ‘miracle’ I mean that you need to overcome so many obstacles before you can actually shoot, and often, despite the best intentions, movies aren’t made for many coincident reasons. The reason why Antonioni and my mother Sophia Loren did end up teaming together was because of my growing report with Michelangelo. Michelangelo and I had many lunches together, many of those at home with my parents, and my mother, in particular, was present: during one of these lunches it born the idea of my mother and he collaborating together. My mother was always in search of directors with big visions, and with a clear idea about how to use her iconography to serve their vision: a movie with Antonioni and my mother would have been, as everybody can easily imagine, magnificent. My mother Sophia had a few regrets in his life: one of them was not working with Luchino Visconti on La Monaca di Monza (The Nun of Monza), another one not having the opportunity of collaborating with Antonioni despite his productive bond with my father Carlo. However, neither Destination: Verna was eventually shot. In our business, it is always impossible to tell ‘why’ a movie is not made: you start with the best intentions, but something happens. It’s not right anymore, or the stars do not align: the pain of not making a much-prepared movie is real, but if you look to precise reasons, it’s hard to point your finger at anything. It’s a bit like a relationship, it’s hard to understand why you fall in love, sometimes it’s easier to understand why you did fell out of love but there may be ten more unconscious reasons why it did not work out, that you would never know. The same thing happened for Verna, something evaporated, and Michelangelo never shot that final script. However, Destination: Verna is surely a movie that one day I would like very much to direct.

The final part of the career and of the life of Michelangelo Antonioni was accompanied by a handful of key figures, such as cinematographer Alfio Contini, who died last years, producer Felice Laudadio, Italian actor Kim Rossi Stuart and more importantly his wife Enrica Fico. With which one of them you had the chance to collaborate? How was Enrica Fico present, in the work and in the life of her husband?

I had not the chance of meeting neither Alfio Contini nor Kim Rossi Stuart, but I met several times Felice when he was running Venice Film Festival. My relationship was always with Michelangelo and with Enrica, who was truly the closest person to him. Enrica was Antonioni’s whisper, she knew him, really knew him inside and out, and she was present in his life until the very end. What was very beautiful it was that especially after the stroke she created an environment that allowed Michelangelo to direct his movies and to be able to exercise his art and his passion. Enrica facilitated many things, in order to allow Michelangelo to truly be himself at his best. She and I related well, too. At the beginning of my collaboration with Michelangelo, I was asked to write letters on their behalfs, such as business letters, or letters about casting: however, the first letters that I wrote were too long, with too many words, and I remember that Enrica came to me and told me ‘Michelangelo likes letters that are simple, inevitable and strict to the point’. Enrica taught me how to write letters, how to express myself with fewer words possible, something she herself had learned from Michelangelo at the time he could write and speak fluently. I still think about that teaching, when I make movies, and I imagine the shots as if they were words, striving to shoot scenes with as few shots as possible, only with shots that become ‘inevitable’. It has to be simple, and pure, and direct-to-the-point, otherwise I’d miss its essence. Part of the simplicity and the ‘inevitability’ of what I shoot I learned from writing letters on behalf of Michelangelo Antonioni, trying to find right words getting rid of any excess.

In the same period of your experience as Antonioni’s personal assistant, in 1998 you made your directorial debut with the short film Liv, which premiered at Venice Film Festival, where both Antonioni and Robert Altman were credited as executive producers. How did Liv was born and what was it about? What were the contributions from Antonioni and Altman to your first project?

Liv was my thesis film at USC. It was a story of this young woman whose mother passes away from cancer, from a certain specific kind of cancer, and as a result of this loss Liv shoots her life down: she does not project herself in any kind of future. At a certain point, life suddenly puts in her path a man, with whom she has not a sentimental relationship but a physical relationship, and that physicality makes her feel a desire to start living again, to re-set her life. I never expected that both Michelangelo Antonioni and Robert Altman got credited into this little film of mine, I didn’t have the arrogance to ask such an honour, but, because of my link with Michelangelo and because my mother had recently done Prêt-à-Porter with Altman, they both happened to see Liv completely independently. After the vision, they both called me to talk to me about it, and, thanks to their strong encouragements about what I shot, I gathered my own courage to ask them if they would appreciate being mentioned somehow in the credits of Liv: they had helped me and I wanted to credit anybody who helped him in that creative process. I was ready to involve them with any credit they thought would have been appropriate, and both Antonioni and Altman came up, independently, with the proposal of being mentioned as ‘executive producers’. I was completely overwhelmed by this double proposal, and the credits ended up becoming the most important element of my short movie Liv, surely the only movie where Altman and Antonioni are credited together! It was beautiful that was these two masterful filmmakers saw the work of someone who was starting out at that time, and, through encouragement, they gave me the chance to symbolically include both of them in my first work.

After your ‘apprenticeship’ with Antonioni you had an important career as a film director, which included your feature-film debut Between Strangers, two other important short movies such as Il turno di note lo fanno le stelle and The Human Voice, and the recent The Life Beyond, co-produced by Netflix, nominated for the Golden Globe as the Best Foreign Langue Film. Looking back in time, what do you think that have been the directorial and human teachings that the collaboration with Michelangelo Antonioni left you?

Posters of The Life Ahead, Edoardo Ponti, with Sophia Loren (2020)

First of all, his first legacy, to me, is Michelangelo’s indomitable desire, his need to look at life, look at the relationship, which I learned through the eyes of a person who was always seeking out the core between people, the authentic truth of what it is that is happening between them. That’s one thing. Another unforgettable teaching is this combination of looking at life through a lens, trying to capture the most authentic grades of relationships, but at the same time, looking at life from 35,000 feet, from a bird -side view, so you can always see the patterns of this relationships, to get larger perspectives about how these relationships connect to the larger side of things. This combination of the granular and the universal is something that Michelangelo had at 100%. Maybe I was prone to learn it, maybe there was something in me that was ready to receive it, but he undoubtedly was the one who showed me how to achieve that.

During the months you spent together with him, what has been the moment when you felt the closest, to Michelangelo Antonioni?

When he was in California for the preparation of Just to Be Together, he was renting John Malkovich his house in L.A, next to Hollywood. One day, we were sitting in the living room, and the living room had this huge day window, overlooking a garden. It was fall, so the colours were not bright, the grass was not very brilliant, and the leaves fell from the trees to the garden. Here in California, you have gardens with blowers, and gardeners blow the leaves into piles in order to throw them away. One of my tasks with Michelangelo was to read to him, and read with him, the scripts, to really understands his vision as much as possible, so we were doing this exercise, but, that day, I noticed that his attention was not focused on our work, he was constantly looking to the garden, with the leaves shaken by a gardener, using the blowers. The wind was blowing

these leaves, and, because the window had this rectangular shape, it was almost like the 2.39:1 aspect ratio. I myself looked at what he was looking at, and I understood that frame was exactly Antonioni’s frame. This gardener, blowing the leaves, and the sound of the blowers, and the sound of the wind in the garden, all put together in this kind of suspended, private moment of this man, doing something that tomorrow the gardener would have to do again because the leaves will fall again: it was poetic, essential and useless. He felt in love with this moment, and I kind of elbowed him – we had this kind of relationship, I could easily elbow him – and I said ‘ti place, eh?’ (‘you like it, don’t you?’): he looked at me and made a gesture of appreciation with his hand. I will never forget that moment. The reason why we make movies and we watch movies is to see the world with the eyes of a filmmaker, to see the world with the eyes of that person because his view inspires us: and how beautiful it was to capture that moment when Michelangelo Antonioni noticed something that to anybody else’s eyes would have just been ‘Monday’, and by simply looking at it turned a Monday into art – I will never forget that.

After the withdrawal of both Just to Be Together and Destination: Verna, how did Michelangelo Antonioni and you say goodbye to each other?

When he was preparing Just to Be Together, Antonioni always wore this brown, silk scarf. The last day, a few hours before he left to go back to Italy because the movie eventually fell through, Michelangelo, Enrica and I had a moment where we were going to say goodbye: and I wanted to spent as much time as possible with him, I was so sad to see him go because I had created such a strong bond with him, so we hugged. As we said at the end of the Eighties Michelangelo had a stroke, which left half of his body somewhat paralyzed, but he knew how much I admired his scarf, and, with his good hand, he pulled the scarf until it felled off his neck to his hand, and he gave it to me. I still have it, of course. It was a beautiful moment, a moment of friendship and generosity which I will never forget and still when I think about it, this memory moves me.

Michelangelo Antonioni died on 30th July 2007. Beyond the Clouds remained his final feature film, but he kept shooting some significant shorts until 2004. What do you remember of your last meetings? What do you think has been his legacy, in Italian and international cinema?

Sophie Marceau and John Malkovich in Beyond the Clouds, Michelangelo Antonioni and Wim Wenders (1995)

I remember going to his house in Rome, maybe a year and a half before he passed away, and no matter in what conditions he was that day – strong, or fragile – Antonioni was always creating. His apartment was always filled with canvases: on the floors, the larger ones, on the walls, the smaller, and all of these canvases were at various levels of completion. Again, how amazing it was, that this man could not stop himself from creating! You can’t help a few things in your body, you can’t help breathing, you can’t help your heart beating: it was like this to Michelangelo, when it came to creativity. He could never stop, even if he ever wanted to. It was beautiful: looking at his face, you always saw how his eyes had the electric energy of a teenager, in his gaze anything was possible. The older one gets, the more usually we are victims of regrets, of bitterness, but there was none of that in Michelangelo’s eyes, there was just the desire to look forward, and to create, and to connect, and to communicate. When I last saw him, Michelangelo was still doing that, through paintings, and even if his body was deteriorating, slowly, yet his imagination was ramping up, reflected in those vibrant colours. Until the end.

You had the chance of reading in preview two of the final scripts written and conceived by Michelangelo Antonioni, and you have a wide-spanning knowledge of his cinema. About Michelangelo Antonioni’s scripts, what did impress you the most? What do you think were the most innovative elements of them?

The ambition of them. For many directors, a script is more than a blueprint, the script is the bible. Also for me, the script is the ‘lifeboat’ that assures you as a filmmaker that you really ‘have’ a movie: you can rely on the script to know if you have something that automatically would become a movie that will engage the people someway. For Michelangelo, the script was only a blueprint, a stepping-off moment: he trusted the instinct of the shooting process, of what was going to happen on the set that day with the actors. There was such flexibility in his creative process, an openness, which made his scripts more than a ‘way in’ and less than a destination. His screenplays were very ambitious because he knew that, during a day on the set, everything could change: if you consider what actually is the traditional filmmaking process, the ambition is to write something that is not the exact plan of what you are going to do, of something which is only the beginning of what you are going to do. Robert Altman did the same: the final versions of his screenplays were really short. Sometimes the scenes had no real lines because he knew the actors would improvise: ‘Scene 5’, you know, was just a brief description of the dynamics of the dialogues, ‘in Scene 6 something like this will happen but no sure’. If I did that, no producer would give a dollar, but because Michelangelo and Robert were masters, they could, and this made their movies very free! Making movies is like a military exercise: you have to be such a masterful general to move the troupe, the equipment, the actors, to exude such a sense of confidence and inspiration, that, even if you do not have a very clear blueprint such as a ‘classic’ screenplay maybe, your collaborators would go along with you - because there is something about you that people trust, there is a sensibility in you that people do trust, so they are sure that what on the script seems ‘almost nothing’ will actually become something because you see it in the mind and in the heart of your director. That’s amazing, that’s why Michelangelo’s scripts were amazing and that’s why his movies were so meaningful and free.

You eventually had not the chance of sharing a set with Michelangelo Antonioni, but you attended several meetings he had with the potential actors of his planned movies. According to your experience and to what you may have heard from his long-standing collaborators, how did Michelangelo Antonioni address and direct the actors? What do you think that distinguished the performances of the actors in his movies?

Jean Moreau e Marcello Mastroianni in Al di là delle nuvole

I think that, first of all, he trusted them. His main work was to cast them. Like all of us directors, for Antonioni casting was everything, but once he cast somebody he was convinced he could do the role, I think that he gave the performer a lot of flexibility to do his role. If you think about it, Michelangelo Antonioni’s films are all rather intellectual and quite formal in their structure and in their aesthetic ambitions, and yet I never found his movies ‘tiring’ or ‘pretentious’. I think that this happens because he allowed the actors to infuse their characters with their individuality, with all of their idiosyncrasies. If you look to David Hemmings in Blow-up, you see a real man, not only a ‘character’: within Antonioni’s typical frame, a frame which is overtly formal and quite rigid, to see this figure who is so subtle, and human, and spontaneous, adds so much life to his movies. In a way, this granted Antonioni’s movies all of the facets that a formal approach to filmmaking may not give. He trusted his actors to bring all of that spontaneity, and his control over the performers came only when he cast them: he had to be sure that this person filled the iconography of the character, his profile; once he was there, he let them be free, he let them be spontaneous. That’s why his movies do not feel rigid, and the actors do not feel as acting: Jack Nicholson in The Passengers, David Hemmings in Blow-up, Monica Vitti in all the movies they shot together, Alain Delon in L’Eclipse, Jeanne Moreau in The Night are all quite free, quite open, quite spontaneous. And by the way, you had to be a great actor to work with him: once on the set, Michelangelo Antonioni wasn’t going to give you many directions about your performance, you needed to have a good sense of who you are in order to be in a film of Antonioni, if you had not you would have tended to be rigid. Once he cast you, it was all a ‘show me what you got, but I sincerely think that this is the best way to capture the best performances from the actors.

Michelangelo Antonioni was always in search of a ‘film specificity’ in his movies, always seeking to tell a story in a way that only cinema made possible, within frames of great visual beauty and distinguished by a geometrical use of cinematic space. What do you think that has been, pictorial, photographic or cinematographic, the influences of Michelangelo Antonioni and where do you think that his personal, cinematic research was leading to?

I do not feel that I am educated to speak with any authority talking about his influences, there are much better people and movie critics to ask this question. What I can surely say is that Michelangelo had a very very strong sense, obviously, of the imagery; however, I think that people focused too much on that, and not enough on this sense of humanity that he had. People misinterpreted the inability of people to connect in his movies as a form of coldness or as a lack of faith towards humanity, which leads to an ‘aestheticism’ very cold and glacial. To me, that’s incorrect. The image was only one way Michelangelo expressed himself, but in his works, it was equally important what animated him as a human being: the fact that Antonioni’s movies are full of people who cannot connect is a reflection of his own actual desire to connect, with people and with his audiences, and to infuse his movies with his vision of art and his vision of the soul. Michelangelo Antonioni is known by the world as this visual filmmaker, but I have known him as a filmmaker of the heart, and that’s what touched me, time and time again, thinking about my friendship with him, because I saw what moved him, I saw the emotions that would have led to those images: those images were never found in intellectual imaginers, but in something that was moved by his hearth and his soul.

Besides being a true aesthete of the image and of the soul of his characters, Michelangelo Antonioni was very prepared also on a technical level, and his 1980 movie The Mystery of Oberwald was the first feature movie, in the history of cinema, to be shot with analogic technologies, the ancestor of contemporary digital filmmaking, in order to achieve a greater control on the colour.

Monica Vitti in The Mistery of Oberwald by Michelangelo Antonioni

Because Michelangelo was always creating, he was very open to any device to able to shoot without any obstacle, the trucks and all the things. He would have loved to make a movie on an iPhone, I am sure about that. If he found the right story, the right lenses, he would have loved, as an iPhone would have allowed him to create as quick as his mind was going, to be able to capture everything that he was feeling in that precise moment. Michelangelo was open to all technologies, that’s sure. About his famous obsession for colour, I remember my father telling me that one day Michelangelo wanted to paint the grass green and brown because he had his idea of what the colour of the grass had to be: he was an artist, and as an artist, he was determined to portray a world the way he saw it. A colour was surely one aspect of his vision, his palette was greater than his immense attention for image, or for colour, or for people - it was all these things together. What made Michelangelo Antonioni the artist that he was it was not a single aspect of his style of filmmaking, the colour, or the frame-shape, or the writing: Antonioni was a true master of filmmaking because of the way he managed all these different kinds of stuff, from the conception to the post-production of his movies and without forgetting his canvas, in a form which was visually unforgettable and intellectually stimulating. His art came in the form of a balance, of all these interesting aspects, interests, expertise that he had. To serve the story in the right way, at the right time. And that’s art: timing. Timing, discipline, and openness.

Very special thanks to DoP Ferran Paredes Rubio for having allowed this interview.

Thanks also to Tobia Cimini for the technical support and the collaboration during the interview.

Discover our books

Discover on our blog the interviews with directors and cinematographers

Subscribe to our newsletter!

On Suspiria and Beyond: A Conversation with Cinematographer Luciano Tovoli

paperback and ebook

The Great Beauty: Told by Director of Photography Luca Bigazzi

paperback and ebook