Paul Hirsch is an American film editor, has collaborated with directors like Brian De Palma, George Lucas, Herbert Ross, Joel Schumacher, George A. Romero, Taylor Hackford. He won an Academy Award for his work on the original Star Wars (George Lucas, 1977). With De Palma Hirsch worked on eleven films: Hi, Mom!, Sisters, Phantom of the Paradise, Carrie, Obsession, The Fury, Home Movies, Blow Out, Raising Cain, Mission: Impossible, Mission to Mars. He has collected anecdotes of his career in the memoir titled A Long Time Ago in a Cutting Room Far, Far Away (Chicago Review Press, 2019).

Your father, Joseph Hirsch, was a well-known painter whose works are in the permanent collections of major museums in the US, including the Metropolitan Museum, the Museum of Modern Art, and the Whitney Museum. Was he interested in the film process?

Not terribly much. I think he liked going to the movies but was absorbed in his work, and in playing the piano. My parents were divorced, and I lived with my mother, so I only saw him twice a week. But one of those days was Sunday, and we would go to concerts together. I don't remember him ever taking me to a movie.

What can you tell me about your cultural background? You graduated from Columbia University, right?

Before college, I attended the High School of Music & Art, a public school in NYC. It was one of the elite schools run by the Board of Education, and you had to qualify in order to get in. Art students had to present a portfolio of their work, and music students had to audition and take some basic music literacy tests. I took drum lessons in order to qualify and got in. I was in orchestra classes for the three years I was there and developed a lifelong love for classical music, although we also listened to a lot of jazz. When I graduated, I was well versed in musical history, but knew very little of art history. At Columbia, that was my major, I spent many hours sitting in dark rooms looking at images projected on screens and critiquing them. This turned out inadvertently to be great training for my eventual career as a film editor. When I graduated, I applied to and was accepted into, the Columbia School of Architecture. However the summer before I was to begin my studies, I spent several weeks in Paris where I was exposed to Hollywood films presented as works of art by auteurs. This altered my thinking, and I abandoned architecture and sought out a career in the film business.

Was your brother Charles (film producer) who introduced you to Brian De Palma, for the editing of your first movie Hi, Mom! (1970)?

Hi, Mom!, Brian De Palma (1970)

Yes, Charles had talked his way into a job as a junior executive at Universal in New York, and De Palma came to him looking for funding for a feature film. They wound up financing it independently, and it was picked up for distribution by a small company called Sigma III. By that time, I had found a niche as a trailer editor, and they came to me to cut the trailer, which is how I met Brian. I go into detail about all this in my book.

You established yourself during the New Hollywood years. What do you remember from that period?

There was a general feeling of a new generation coming into its own, and the young directors emerging around then formed friendships outside of any professional relationships. I was fortunate to meet many of them through my work with Brian. This led directly to being asked to come work on Star Wars. Again, I go into great detail about this time in my book.

Picture taken during the editing of Star Wars. From left to right, Marcia Lucas (with her back to us), Brian De Palma, Hal Barwood, Gary Kurtz, Steven Spielberg, George Lucas, with Paul Hirsch in the foreground.

You worked with Brian De Palma on eleven feature films: Hi, Mom!, Sisters, Phantom of the Paradise, Carrie, Obsession, The Fury, Home Movies, Blow Out, Raising Cain, Mission: Impossible, Mission to Mars. What was De Palma's main teaching, if there was naturally?

I was 23 and Brian was 28 when I worked for him on Hi, Mom! So we were both learning our trades, although he was far more advanced than I was, but he was still maturing as a director. The main thing I learned from him was his use of the point of view shot, which puts the audience inside the character's mind. She looks, she sees, she reacts. We can infer her thoughts through this sequence of shots. It brings the audience into the story in a more intimate way.

During the editing phase, did De Palma give you advice, suggestions or did he leave you free to work?

Brian was very specific in his choice of camera angles and knew what was needed. He was not a micro-manager in the editing room. He let me do the initial cut as I saw fit, and then make adjustments subsequently. No two people have the same sensibility, so there are always adjustments to be made. But he was very supportive and encouraging.

Brian De Palma, Paul Hirsch, and Tom Cruise on set of Mission: Impossible (1996)

What can you tell me about the use of "split-screen" (a sort of contemporary montage of two scenes in the same shot) in the style of De Palma?

That was entirely Brian's idea. He was fascinated by it and used it successfully in some of the films we did. Later, he used split diopter lenses to achieve a similar effect. As film stock became faster, that is, more light-sensitive, cinematographers started worrying less about parts of the frame being out of focus, and shot in lower and lower light levels. The result was that if you framed two subjects together who inhabited different planes away from the lens, one of them would be out of focus. This led to rack focusing, which is overused now like zoom lenses were for a while. You look at old films, and nothing is out of focus, even if you have characters close to and far from the lens in the same shot. I miss that.

A split-screen in Brian De Palma’s Sisters (1972)

Already at the beginning of your career, you won an Academy Award for your work on the original Star Wars, which you shared with Richard Chew and Marcia Lucas. What has this great prestigious award meant for you?

It was extraordinarily helpful in making myself known to the film community. Ever since I am regularly introduced as "Academy award-winning." And they say that winning an Oscar adds five years to your life!

After the Academy Award, thirty years later, you got a nomination for the film Ray directed by Taylor Hackford, a biographical musical drama film focusing on 30 years in the life of rhythm and blues musician Ray Charles. How did you live this moment, with more maturity and experience I guess?

My maturity and experience were not that much of a help, since I won the first time I was nominated, and lost the second time. I learned that it is a lot more fun to win!

With Herbert Ross, you have formed another important collaboration in four films: Footloose, Protocol, The Secret of My Success, and Steel Magnolias. What do you remember about Ross? How was it working with him?

Herbert was a very demanding director. He had been a choreographer, and he is known (by his own admission) to be the cruelest people on earth. But he and I got along very well, after an early contretemps, which I wrote about in the chapter on Footloose. He was the best director of actors I ever worked with and had a sensitivity to performance matched by few others.

A curiosity of mine: The Black Stallion Returns (Robert Dalva) and The Secret of My Success (Ross) were cinematographed by the Italian Carlo Di Palma AIC. Did you meet him?

Editors and cinematographers used to meet when the crew came in at the end of the day to look at the rushes from the previous day. The Black Stallion Returns was filmed in North Africa and anyway, I wasn't hired until well after the shooting had ended. So I didn't meet Di Palma then. On The Secret of My Success, I was based in LA, and the picture was shot in NYC, so again, we didn't have much contact. We did meet briefly when I was sent to pick up a few additional shots during post and Herbert was unavailable, due to his wife's illness. I don't remember much about him, although I thought his work was exceptional.

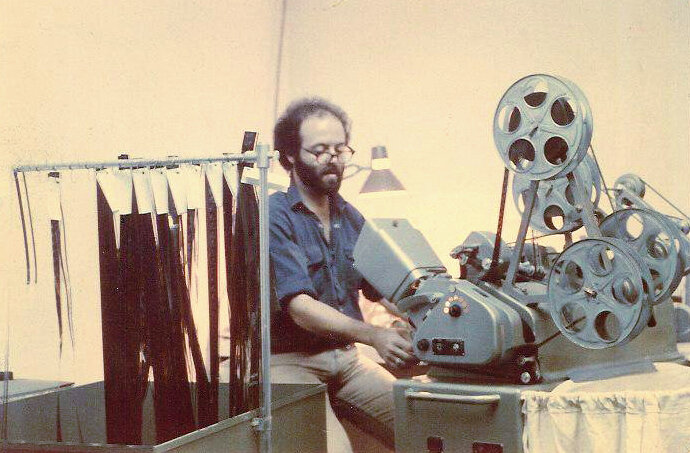

Paul Hirsch on the set of Empire Strikes Back, London, 1979

The cover of Paul Hirsch’s book

You have also worked with directors like Joel Schumacher, George A. Romero, John Hughes, and in the last few years with Duncan Jones on Source Code and Warcraft. Your last official film was The Mummy directed by Alex Kurtzman?

I helped out my friend, producer Mark Gordon, on The Nutcracker and the Four Realms in 2018. That was my last project.

Tina Hirsch is your ex-sister-in-law: is she an editor too?

She was but is retired now. For many years, she was president of the American Cinema Editors, ACE.

Your son Eric and your daughter Gina also work in the film industry. You also worked together with Gina, right?

Yes. It was one of the great joys of my life. She is editing for Ava Duvernay currently. And my son Eric just won two Emmys for his work on The Queen's Gambit.

Which of your films did you like the most?

That's like asking which of my children I love the most. I have fond memories of many of them. The ones later in my career, not so much.

How has your work changed, from old Moviola to modern software?

Editing is not about the tools. Just like writing. No one would suggest that Shakespeare would have been a greater writer if he had a word processor.

Paul Hirsch wins the Academy Award for his work on Star Wars (George Lucas, 1977)

Did you get to know the Italian editors like Pietro Scalia, Ruggero Mastroianni, Gabriella Cristiani, Nino Baragli, Roberto Perpignani in some convention, festival or on another occasion?

I met Pietro Scalia when he was an assistant on one of Oliver Stone's films. But I can't say I know him well. I've never met the others.

You are the author of a memoir titled A Long Time Ago in a Cutting Room Far, Far Away. Where did the need to tell your career come from?

I had been telling these stories for many years and decided I should write them down. I was on location and alone, and I needed something to occupy me in my spare time. I reckoned that people might be interested to read them, and judging by your questions, I was right.