«The most famous unknown actor in the world»: with these words Sir Arthur C. Clarke, author of The Sentinel from which Stanley Kubrick drew his 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), summed up the career of Daniel "Dan" Richter (Darien, Connecticut 1939), American actor, mime and photographer (son of the well-known cartoonist for «The New Yorker» Mischa Richter), who went down in cinema history with his interpretation of man-ape in Kubrick’s masterpiece, for The Dawn of Man sequence, where he played Moonwatcher, the leading monkey. After the film experience Richter becomes one of the best friends of Yoko Ono and John Lennon: to be exact between 1969 and 1973, he became their official photographer (his photos of various album covers of that period), appearing and collaborating among the other also in Imagine, a 1972 documentary, directed by Lennon and Ono (and Steve Gebhardt).

For Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), you have been called first as a consultant and then as a choreographer for The Dawn of Man sequence, where you played Moonwatcher. It's right?

Yes, that’s true. Through a mutual friend, I had been asked to have a meeting with Stanley. He had made many attempts to put the Dawn of Man sequence together and none had worked. In a conversation with Arthur Clarke they realized that they had never talked to a mime about it. My name came up and Stanley asked for me to come out to the MGM studios to let him pick my brain. We hit it off and my approach to treat it primarily as an acting problem, using well-motivated movement, appealed to him. I gave him a demo and he pretty much hired me on the spot.

On the set of The Dawn of Man sequence, 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

Photo: probably Stanley Kubrick - Courtesy of the Kubrick Family Estate

Is it true that you spent ‒ at the specific request of Kubrick ‒ whole weeks in the London Zoo studying the behaviour of primates?

I spent longer than that. It took over six months to develop the movement. My apartment overlooked Regent’s Park where the zoo was, and I spent a great deal of time there. After I had cast my troupe of man-apes I would take them there as well. During those visits, I became friend with Guy the gorilla and he eventually became the animal control for my character Moonwatcher.

Did you design and develop together with Stuart Freeborn the makeup and costumes of the ape-men?

Stuart was the designer of the costume, but we worked together almost daily. It was a wonderful give and take for many months. The first models he designed were, from my point of view, too heavy and awkward. Since I was trying to use acting values to bring the man-apes to life, I needed to have as much freedom as possible so the motivated movements would reach the audience on an intuitive rather than an intellectual level. You can never design a costume that will on its own be believable. If the audience goes with the acting values, they will suspend disbelief and then you have them.

Men-apes with costumes designer Stuart Freeborn. Collection of Stuart Freeborn

What do you remember of the front projection used by Kubrick for filming The Dawn of Man sequences?

That’s a big question. We did so much technically to get the system to work and then to be able to perform in front of it that there is so much I could say. The biggest issue for me, both as the choreographer and as the lead performer, was to be able to keep myself and my guys functioning at our best under very difficult conditions. Because the front projection had to send enough light through the 8 x 10 transparencies to fill the 80-foot-wide screen, there was a lot of heat generated. Also, adding to the heat, was the immense amount of lighting used on the set so that the colour temperatures would be right so that the background and set would look as though they were one. We were in masks and costumes that we had to move in with high levels of energy. The acting union had already severely limited how long outtakes could be. We had nurses and helpers standing by to cool us with high-pressure hoses of compressed air stuffed into our costumes at the end of each take. The temperatures on the set were very high. It was also very dusty which got in our eyes.

Man-apes Simon Davis (Keith Denny) and Richard Woods. Polaroid: Stanley Kubrick - from the collection of Richard Woods

On the right: Original Choreography Notes. From the collection of Dan Richter

Do you remember the cinematographers Geoffrey Unsworth and John Alcott?

I saw Geoff a couple of times, but he left soon after I arrived. I spent a lot of time with John and got to know him quite well. I saw him from time to time after we finished the picture.

What do you remember about Arthur C. Clarke, the author of The Sentinel, from whom Kubrick made the film?

I first met Arthur the day I started working in 2001. I had just moved into my new office that had nothing in it but some desks and a telephone. There was a knock on the door, and it was Arthur who had come by to welcome me onto the picture. «I bet Stanley hasn’t even given you a script», he said as he passed one to me. We talked for quite a bit that first day and we became friends. He was only around a few times for the fourteen or fifteen months I worked with Stanley, but we remained in contact and I saw him in New York and Sri Lanka. We remained friends until his death.

Stanley Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke working on 2001 in Stanley's apartment on Central Park West. From the collection of the Kubrick Family Estate

What do you remember of the director Stanley Kubrick, out of the set?

Well, I remember laughing a lot. Endless conversations about the picture, and all kinds of other things from Beat poetry to Napoleon. He had a voracious interest in everything. Christiane wouldn’t let him smoke so we would go for walks around the studio and he would bum a cigarette from me as we talked.

The sequence in which Moonwatcher throws the bone to the ground, learning to use it as a weapon, is one of the most famous in the history of cinema. A Kubrick's brilliant intuition will transform the bone into a spaceship, with the most famous use of temporal ellipses in the history of cinema (thus making a leap of millions of years). What do you remember of that epic moment?

Stanley was always looking for those special moments. He once said something to the effect that if you can find five or six of them and string them together you have a film. When we worked, he was always looking to find something new to use. I can’t think of a director who did more detailed preparation than him, but once he began shooting, he was always looking for something to happen that he could develop and take to a new level. The bone sequence is a perfect example. I was supposed to have the idea put in my head by the aliens to pick up a bone and start using it as a weapon. I knew since this would be the first time that Moonwatcher would pick up a tool, he would have to experience what it all felt like. I decided to play with it at first before I hit the skull and as I was doing that a rib bone I hit popped up into the air. «Sorry Stanley», I said, and he said, «No I like it do it again». We worked at that moment for over a month. When we were finished with the other performers, he did more takes of me with the bone. Then he had a rostrum built outside so he could shoot me from below with clouds behind me. He kept working on that one moment and then one day walking back from the rostrum with Arthur to his office he picked up a broomstick and threw it up in the air and it was complete, he had the throw and that amazing cut forward three million years.

Daniel "Dan" Richter in The Dawn of Man sequence, 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

After 2001: A Space Odyssey, did you see each other again with Stanley Kubrick?

I did see Stanley again during the making of A Clockwork Orange. I had designed a three-headed flatbed editing table for John Lennon and Yoko Ono that we had built in Milan. Stanley was moving from moviolas to flatbeds at that time and heard we had this new table and asked if he could borrow it. John and Yoko were going to Los Angeles for an extended stay, so they agreed to let Stanley use it. I went out to see him as they were putting the table into his garage and we spent the day together. That was the last time I saw him. We did exchange letters but never got together again.

For the Carroll & Graf Publishers (New York, 2002), you published Moonwatcher's Memoir. A Diary of 2001: A Space Odyssey, a diary that follows day by day the filming that saw you protagonist. The preface to the volume is edited by Sir Arthur C. Clarke. What can you tell us about this publication?

I had been toying with the idea of writing about how we made The Dawn of Man and was waiting for Stanley to complete Eyes Wide Shut so I could go over to England and talk to him about it. When he died, Arthur Clarke encouraged me to write it since I was then the last person alive who knew the whole story of how we did it. I did extensive interviews with everyone who was still around so as to capture as much detail as possible, and the result is the story of how we made the sequence.

Before participating in 2001, as a producer and publisher, in 1965 you made the International Poetry Incarnation, held in London at the legendary Albert Hall, together with friends Allen Ginsburg, Gregory Corso and William Burroughs. What was it about?

Allen Ginsberg, International Poetry Incarnation, Albert Memorial Hall, London, 1965

At the time in London, I was publishing the poetry review «Residu» with my wife Jill. It was an exciting period in London and Allen Ginsburg and Bill Burroughs, among other poets and writers, were our friends. Allen had been arrested in Czechoslovakia when the students had made him the King of the May. He was deported and the incident was getting press coverage. We were all talking about it with him at the house of our friend, the writer Alex Trocchi. Allen was going to go on the national news the next day to talk about what had happened to him. We all decided that if he could announce a poetry reading when he was being watched by millions of people, we could get a big audience. Jill and I went looking for a venue the next day. While sitting at the Albert Memorial taking a break and smoking a joint, we looked across at the Albert Hall and something went click in my head. We went across and they had just had a cancellation, so we wrote them a check. Allen announced the reading that night on the tv. When I went back to the Albert Hall the next day, they told me we were selling out. We ended up turning away a couple of thousand people. It was an amazing event with over twenty poets. London was exploding with kids getting high with visions of a new world.

Between 1969 and 1973, you were the official photographer of Yoho Ono and John Lennon (your photos of various album covers of that period), appearing among other things in Imagine, a 1972 documentary, directed by Lennon and Ono (and Steve Gebhardt). What can you tell us about the friendship with Lennon and Ono? Furthermore, is the news for which you are unofficially accredited in Imagine also correct as a DOP?

John Lennon and Yoko Ono during the shoot of Fly in New York. Photo Dan Richter

I was researching the Noh and Kabuki Theatres in Tokyo in1964. I met and made friends with Yoko Ono who translated some of my poetry into Japanese. We ran into each other again about the time I started working in 2001. We ended up taking two side by side apartments together and our families became very close. When she and John got together and bought their estate in Ascot Jill and I joined them and ended up living there with them for three years. During that period, I helped them with a lot of their projects. I didn’t shoot Imagine, I functioned more as a line producer. I did shoot the covers of the Plastic One Band albums as well as some singles. I was very involved in all aspects of the Imagine album and worked mostly as a producer on their experimental films like Fly. Yoko is still a very special friend.

At Tittenhurst, Dan taking a picture of John for the Imagine album. From Imagine, courtesy of Yoko Ono

On the left: Dan Richter and wife Jill at a Poetry Reading in London. Collection of Dan Richter

What can you tell us about the book The Dream is over, with a preface by Ono herself, published in 2012, where you retrace various phases of your life in the London of the Sixties?

It’s my story, but I wanted to focus on my time with John and Yoko. It was an immensely creative period for them as the Beatles were breaking up and John was finding a new voice with Yoko. I was there for most of it. I tell it from my point of view of an art world friend of Yoko’s not a rock and roll guy.

You now live in California, Sierra Madre, where you are an AMGA certified rock climbing instructor. Exact? How is this passion born?

I have climbed mountains all my life starting at about seven years old. Now that I’m retired and in my eighties, it’s great to be around young climbers. Whatever else I’ve been, I’ve always been a teacher.

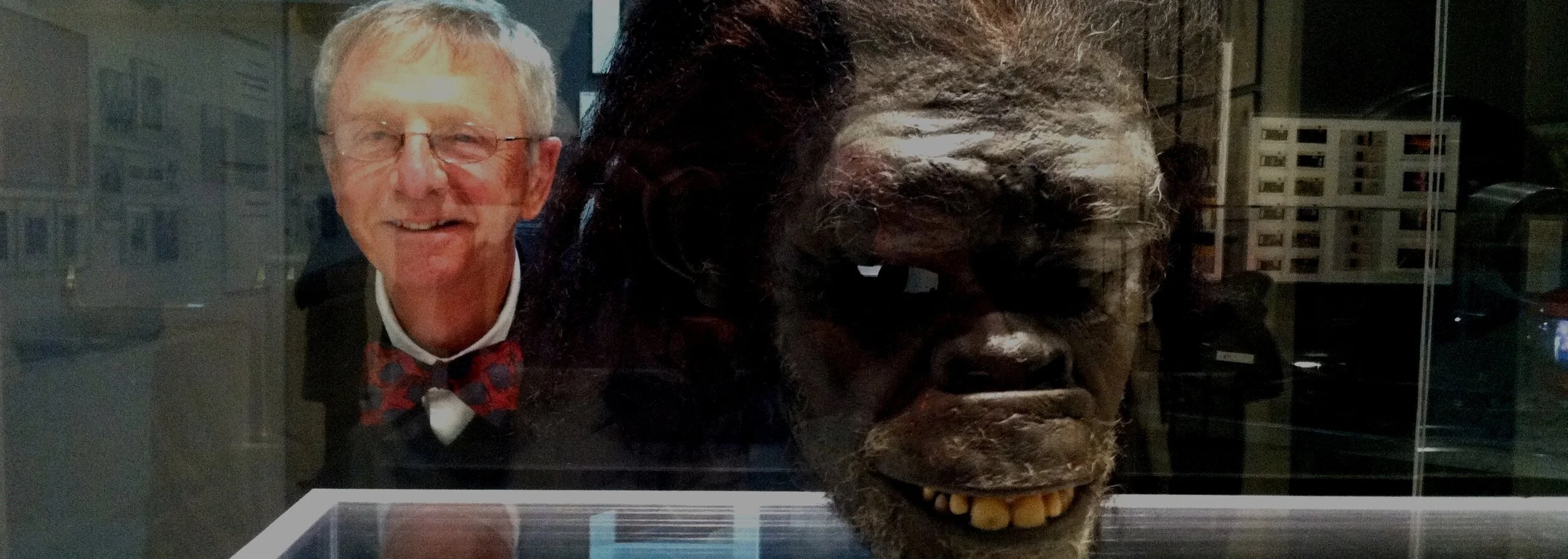

Douglas Trumbull (special effects), Dan Richter, Katarina Kubrick and Keir Dullea January 2020 at the 2001 Show at the Museum of the Moving Image (MoMI) in New York

Discover our book! and sign up to our newsletter

Active Light: Issues of Light in Contemporary Theatre

paperback and ebook

On Suspiria and Beyond. A conversation with cinematographer Luciano Tovoli

paperback and ebook